Melissa & Ann: Navigating America’s Tangled Health Care Safety Net

Two women living in Southern California experience the challenges and benefits of being enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid.

Melissa

“I have spent my life waiting in doctor’s offices.”

As a child, Melissa sat for hours in doctor’s offices. She learned to

count the gray, plastic chairs in the waiting room and trace the lines

and curves on each person who filled them. Melissa’s mother had

diabetes, and the disease’s complications required repeated trips to the

doctor throughout Melissa’s childhood.

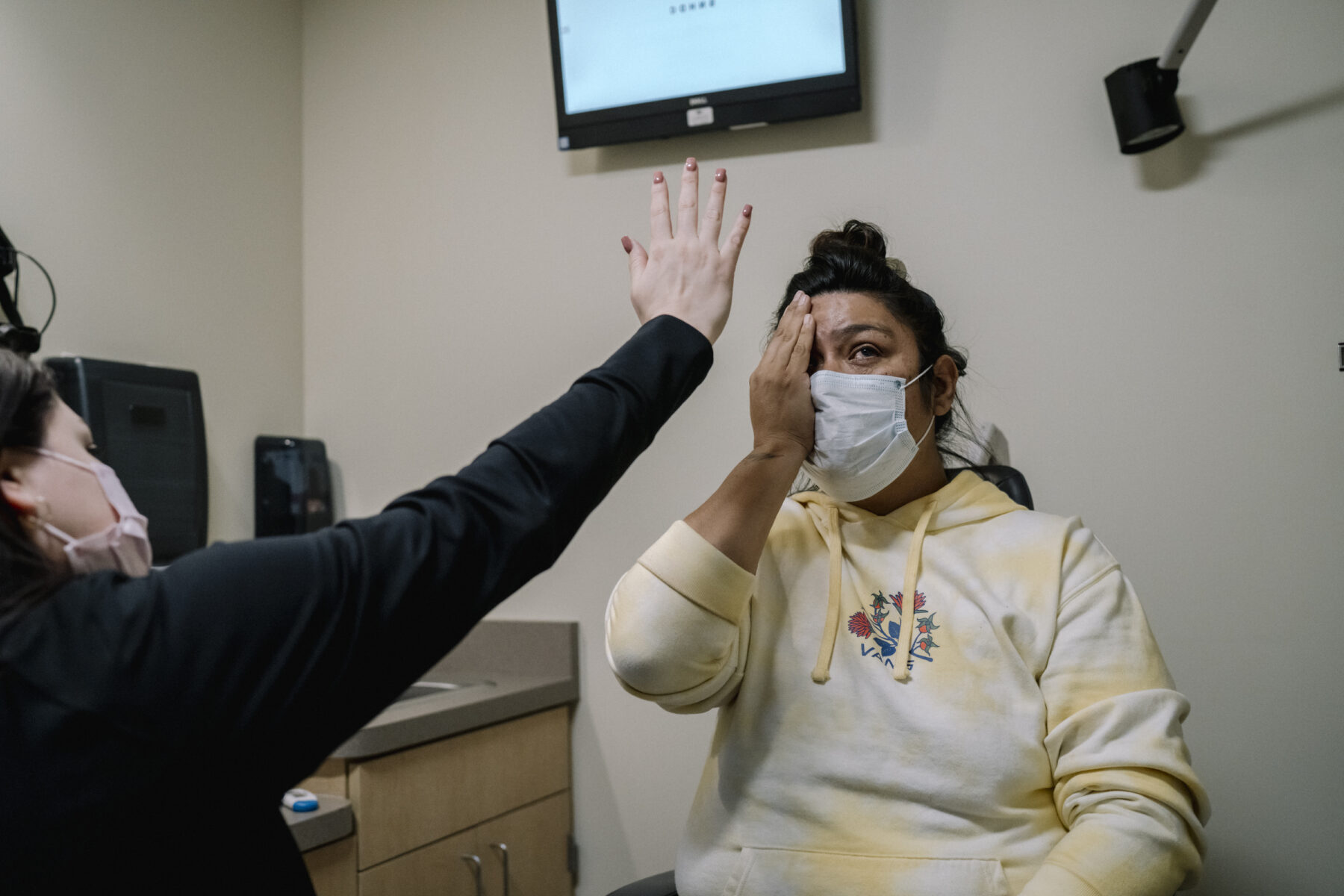

As an adult, Melissa developed the same disease, one that stole her eyesight and thrust her into a world of complex health care systems where navigating coverage, doctors, and treatment is a daily, delicate balancing act.

Melissa, now 41, is among the 12.5 million American adults with disabilities and older adults who receive coverage from both Medicare and Medicaid, a population often called “dual-eligible” in policy circles. Because Medicare and Medicaid are two large, fragmented systems that are not designed to work together, dual-eligible individuals often fall through the bureaucratic cracks. As a result, this population experiences some of the worst health outcomes of any other group in the United States.

Melissa first filed for Medicare coverage a decade ago after experiencing abrupt vision loss. Melissa was grateful to gain insurance she defined as “posh” compared to her lack of coverage before — but she couldn’t escape feeling like she wasn’t accessing all the help she needed.

A mother of six from San Bernardino, California, Melissa has always hustled to survive. She worked multiple jobs since her teens — first as a telemarketer, then in restaurant management, and then in daycare while raising her four children and a set of twin boys as a single mom.

Melissa is bubbly, upbeat, direct, and commanding — a personality that shields her lifetime of trauma and distress. Early one morning in 2008, carrying a check to last her through the week, she buckled her children into her SUV and drove away from the domestic violence she had endured for years. After escaping, she used drugs and alcohol to cope. In 2013, as her life fractured into pieces, she also began to lose her vision. Within a few short weeks, Melissa was nearly blind. Despite six surgeries, doctors could not save her eyesight.

"The shock of going from being a sighted person to being blind almost overnight was enough to really just take me out,” said Melissa. She was left in the dark to navigate her health care, sobriety, and motherhood in the dry California desert."

The combination of her income and now disability — blindness — made

her eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. While she considered this

coverage to be a gold standard of health care, the enrollment process

was incredibly challenging; Melissa finally got access to Medicare and

Medicaid benefits three years after she first became blind. She was

promised a counselor to help her navigate the programs but has yet to

hear from one. No one even took the time to explain her coverage

options.

“The shock of going from being a sighted person to being blind almost overnight was enough to really just take me out,” said Melissa. She was left in the dark to navigate her health care, sobriety, and motherhood in the dry California desert.

In Los Angeles County alone, there are more than 110 plans targeted to dual-eligible beneficiaries. Only a fraction of these options are designed to align Medicare and Medicaid benefits and services for the enrollee. These plans are referred to as “integrated.”

Recent studies reveal that individuals who receive care from fully integrated care plans on average face fewer hospitalizations and hospital readmissions and improved markers of quality care. Despite this promise, none of this was explained to Melissa, and she ended up in separate Medicare and Medicaid plans without access to any coordination between the two.

In her non-integrated care plan, Melissa has faced communication breakdowns at pharmacy counters, on the phone with transportation dispatchers, and in the delivery of diabetic testing supplies. Sometimes the lancets (finger-stick needles used to take blood samples) she receives in the mail are incompatible with their holders or meters. In these cases, Melissa either asks for a courtesy kit from a pharmacy or goes without testing for days.

“Who do I talk to? Where do I go?” asks Melissa. “How do I find out some of the answers to my questions? How come I'm being told one thing, and then when I go to put a plan into action, I'm being told a completely different thing?”

“Some of the downfalls to being dual-eligible are trying to get both insurances to see eye to eye,” says Melissa. She likens her insurances to a pair of shoelaces where one side cannot create a knot with the other.

Melissa even experiences communication breakdowns regarding her insurance status. Although she is fully covered, office staff often tell her she does not have Medicaid, which covers out-of-pocket payments, and request that she pay for her prescriptions. “I just pay my co-pays. If they say I have them, then I have them. It takes too much time to try and battle insurances.”

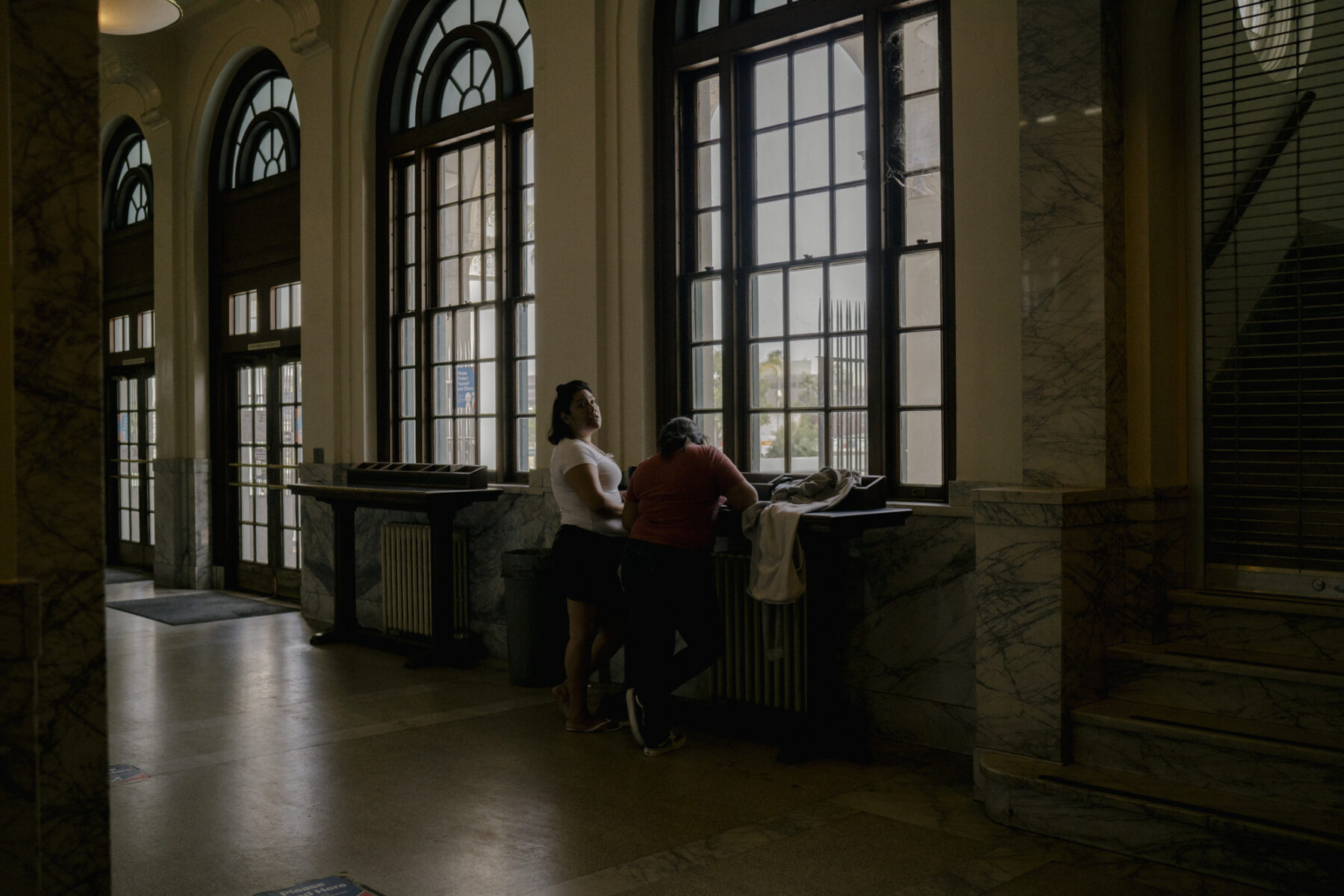

Melissa and her children have changed housing multiple times each year, which also complicates their ability to get to work, school, and medical appointments. They struggle with communicating with the Medicaid-supported transportation providers like ACCESS or Medicaid-contracted Ubers. Melissa has missed rides with contractors because Uber drivers were not alerted to Melissa’s blindness and often arrived and left too quickly. At times Melissa has had to choose between organizing her own appointments and those of her children, often opting to prioritize theirs. The difficulty of transportation can require that she and her children dedicate an entire day for one medical visit, leaving during daylight and returning home in the dark.

For Melissa, managing her care can feel like a full-time job in a two-system plan with limited communication between them. She receives dozens of thick marketing pamphlets per week for health plan alternatives but often does not open them. She worries that if she attempts to change plans, her choice may further complicate her care and take her away from her current doctors.

“Some of the downfalls to being dual-eligible are trying to get both insurances to see eye to eye,” says Melissa. She likens her insurances to a pair of shoelaces where one side cannot create a knot with the other.

Despite hurdles of the two systems, Melissa is pleased with the care she receives from her physicians and specialists. While she has to access care from five different health systems for her quarterly checkups, she firmly believes her doctors are allies and share her goals of longevity.

“The benefit of being dual-eligible is just really great doctors, a

really good group of men that are dedicated to overseeing my health

care,” says Melissa. “It does not get any better than the team I’ve got

now.”

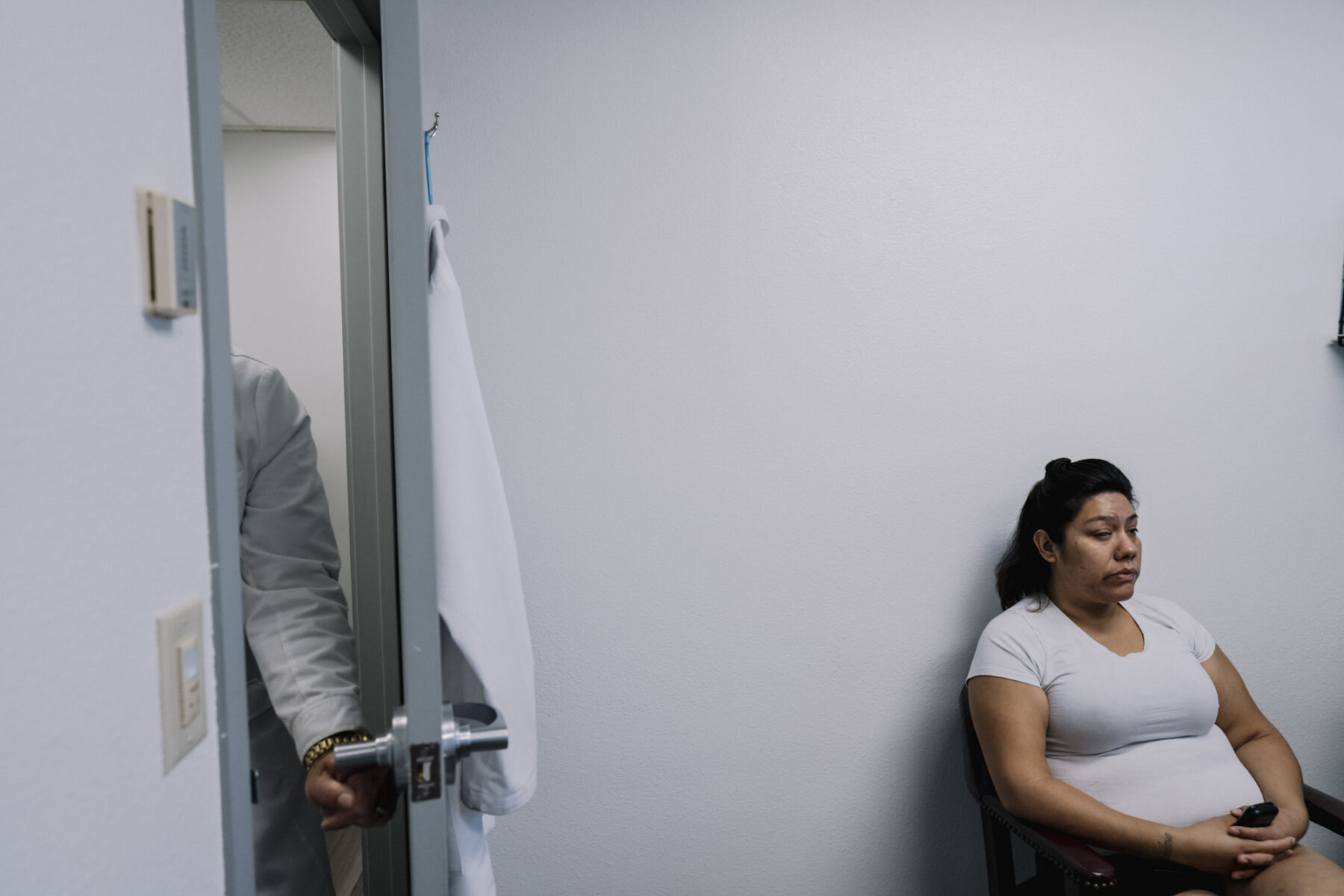

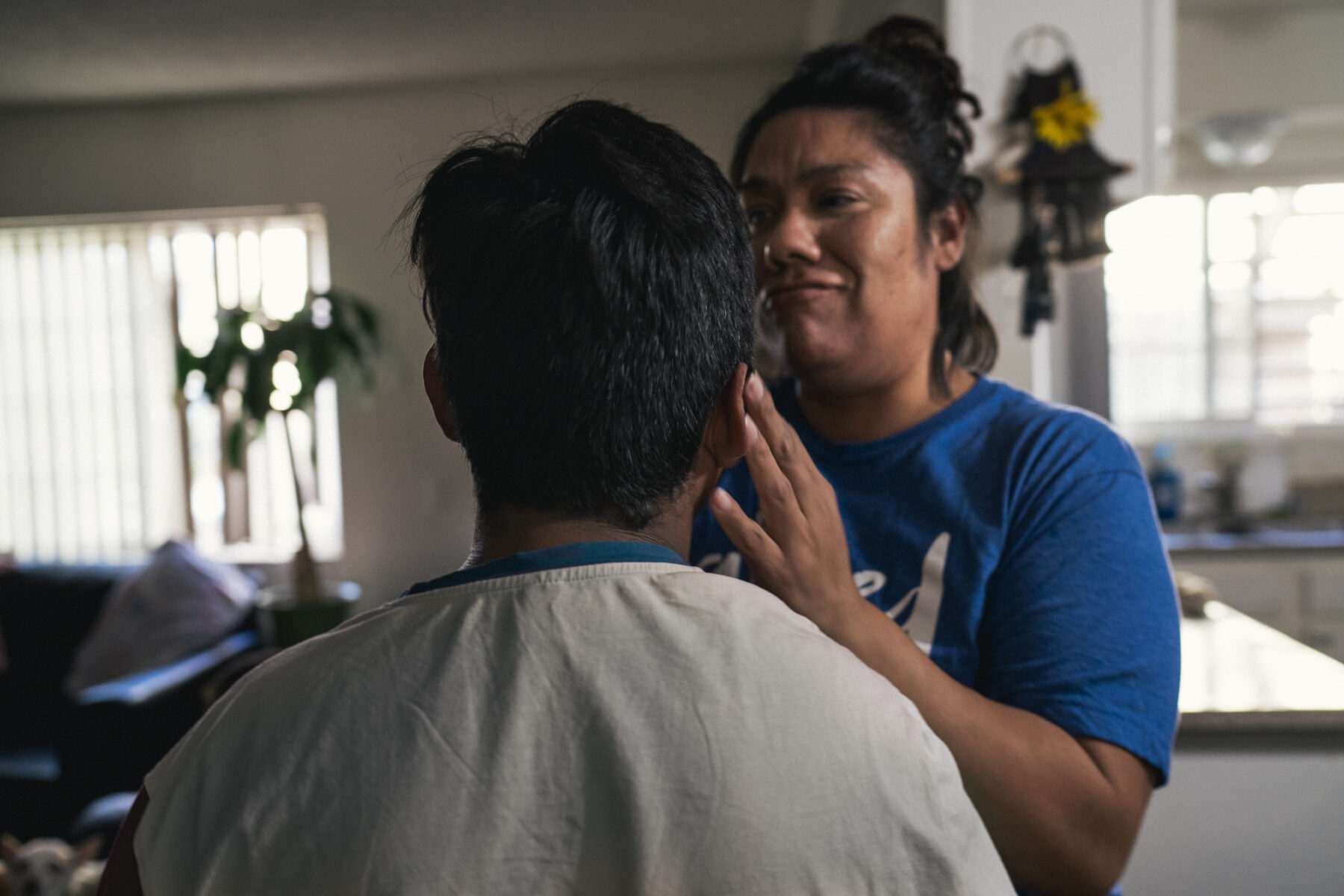

One of Melissa’s children is present for each appointment. Angie, 18,

or Jacob, 15, sits next to Melissa or stands in the corner while

holding her purse and texting about math homework. They are part of an

interdependent family and are partners in their mother’s care, guiding

her down clinic hallways or up hiking trails with her hand on their

shoulders. Her children also keep track of her medical progress and

rejoice when her endocrinologist reports an improved A1C score, a test

used to monitor blood sugar.

“She gets all happy for herself. And I get happy, too, because I know that stuff is what makes her really enjoy going to the doctor's office,” Angie says. She worries when someone other than her children accompany her mom and fears they would not guide her the way her children do.

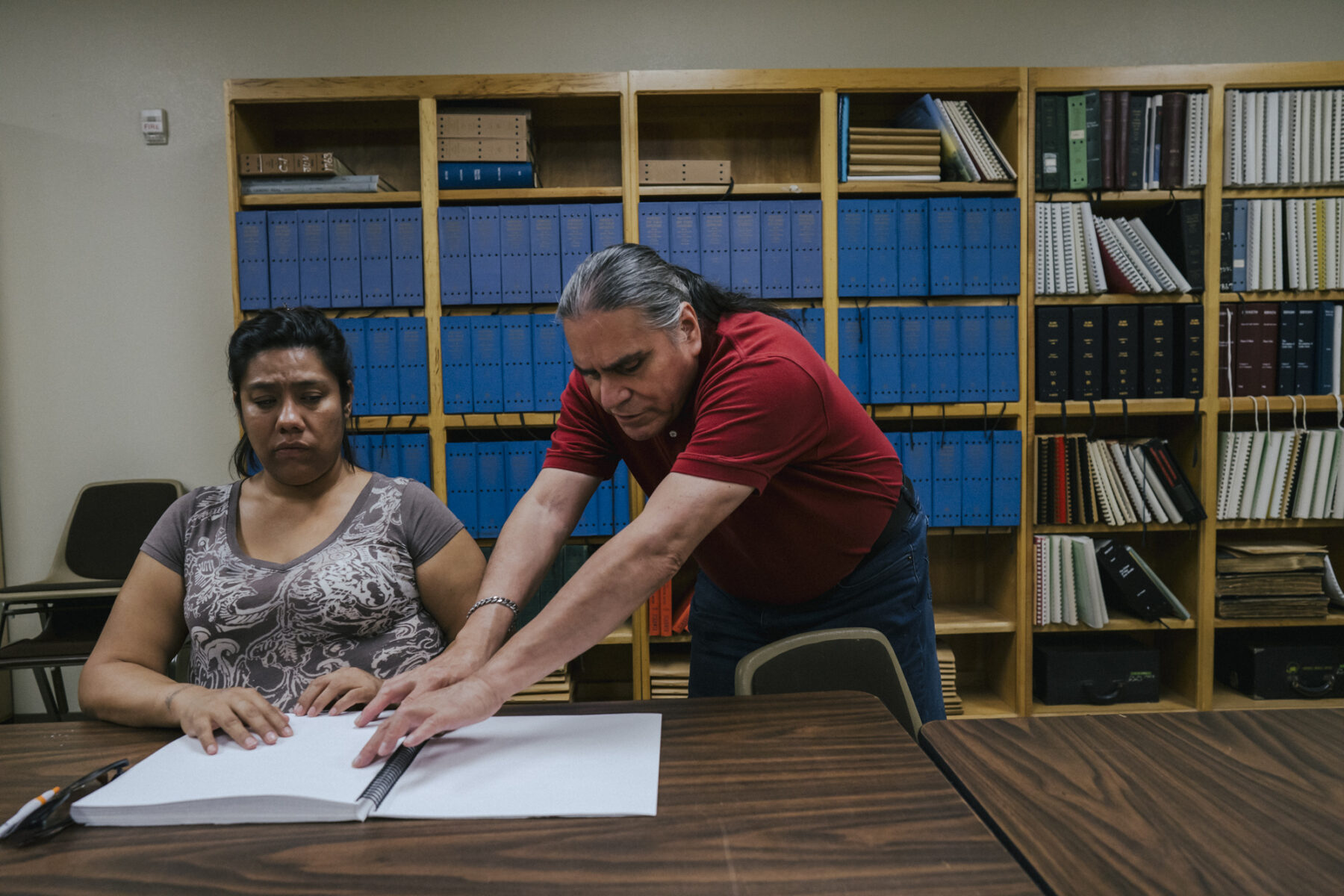

Ten years after losing her sight, Melissa made a decision to celebrate her blindness and increase her independence through training at the Lighthouse for the Blind, a nonprofit organization serving the visually impaired in San Bernardino. She craved connection with other people who knew what it felt like to constantly reach for the walls around them. There, Melissa held her first Braille book, made egg salad in a cooking class, and learned to use a smartphone.

It was at the Lighthouse where Melissa met Scott, a man of a similar age, who was also taking classes; they began dating.

“It’s been a struggle. But I’ve overcome a lot of challenges and obstacles in my life to really just rejoice about where I’m at today in my life and my blindness.”

Melissa aims to learn skills in Braille and technology at the Lighthouse to then take into an associate’s degree program also offered to her through the Department of Rehabilitation. She hopes to eventually become a crisis counselor to aid people out of violent situations and into stability.

Melissa credits her faith as the bedrock for her unwavering optimism. She has become increasingly connected to her church, which has helped her cope with her memories and ongoing daily stress. “God can do what no insurance can.” She meditates on the floor of her studio apartment and listens to the Bible through an audio player while her kids are at school.

“It’s been a struggle. But I've overcome a lot of challenges and obstacles in my life to really just rejoice about where I'm at today in my life and my blindness.”

Ann

When Evelyn unpacked Ann’s suitcase full of thick wool sweaters, she assumed that the newest resident of the group home in Hawthorne, California, originated from a cold climate. She neatly placed each sweater in a dresser, without learning anything more.

Fifteen years later, Evelyn knows Ann intimately. But she still does not know her history. Ann has a developmental disability that impacts her ability to easily express herself through words.

Ann has no living relatives. House aides Evelyn, Mary, and Queen, and the administrator, Darlene, are like surrogate family members.

“We are her family,” said Mary, who has been a care provider in this home for 18 years.

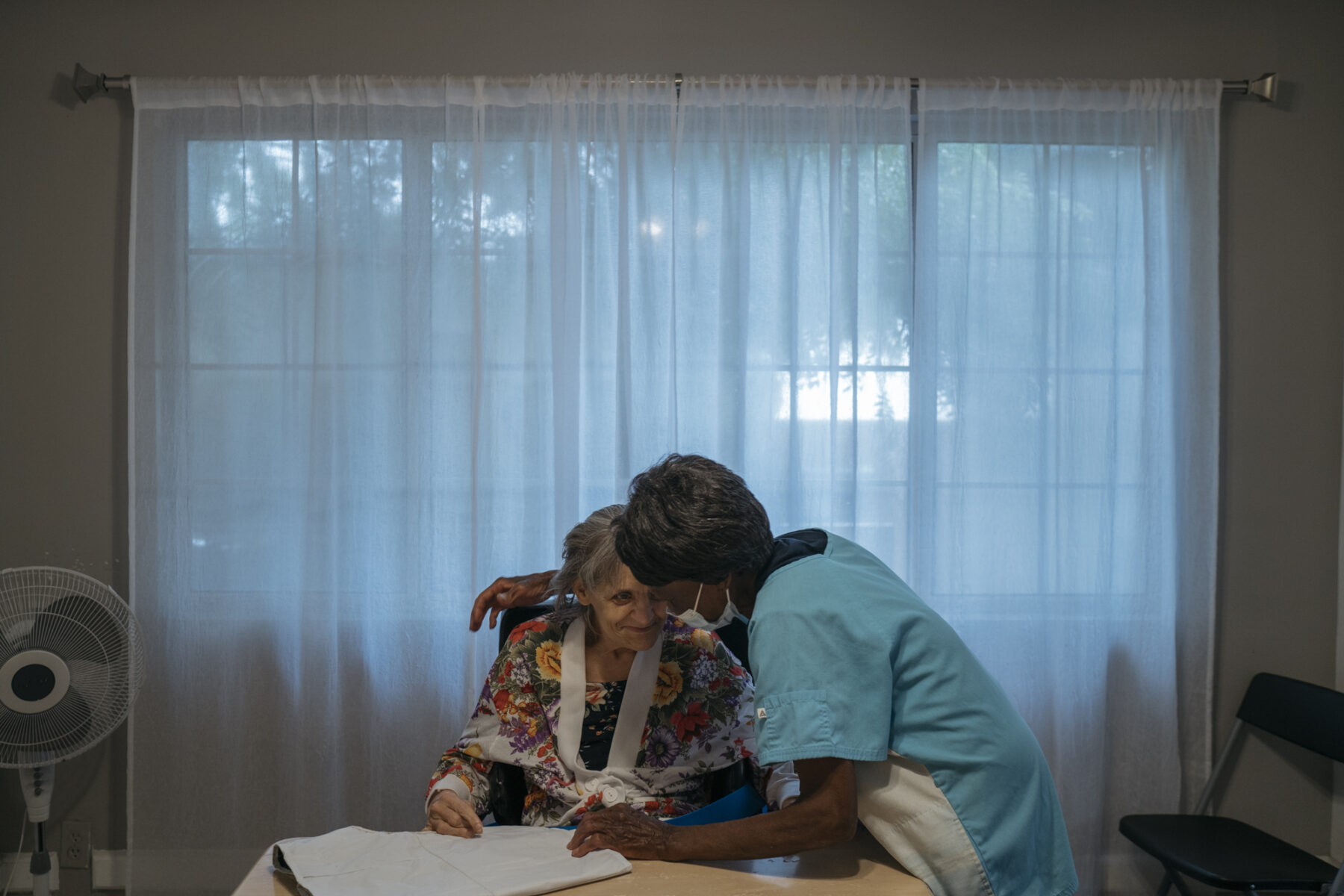

Ann, now 72, is a keen observer who sits in the living room and watches the comings and goings of the house. She is the first voice to greet any visitor. She makes eye contact with a new or known face, delivering an emphasized, “Hello, how are you?”

It is a calm and peaceful home with six adult residents with developmental disabilities and two caregivers per shift.

Five of the six women are mostly non-verbal. But each resident makes her presence known.

Norberta, an older resident with a distinct fashion sense, asks one caregiver in Spanish if her mother purchased her necklace for her. Juliette, one of the youngest of the group, paces around Ann, who continues to take in the movement around her. Ann loves babies and young children and sits by the window yelling “baby” as children are dropped off at a nearby day care. On warm afternoons, Mary, the house aide, takes Ann to the front of the house to watch cars, pedestrians, and clouds move by. “Look, Ann, a plane,” says Mary, as she runs her fingers through Ann’s hair, gathering each short, gray strand into a ponytail.

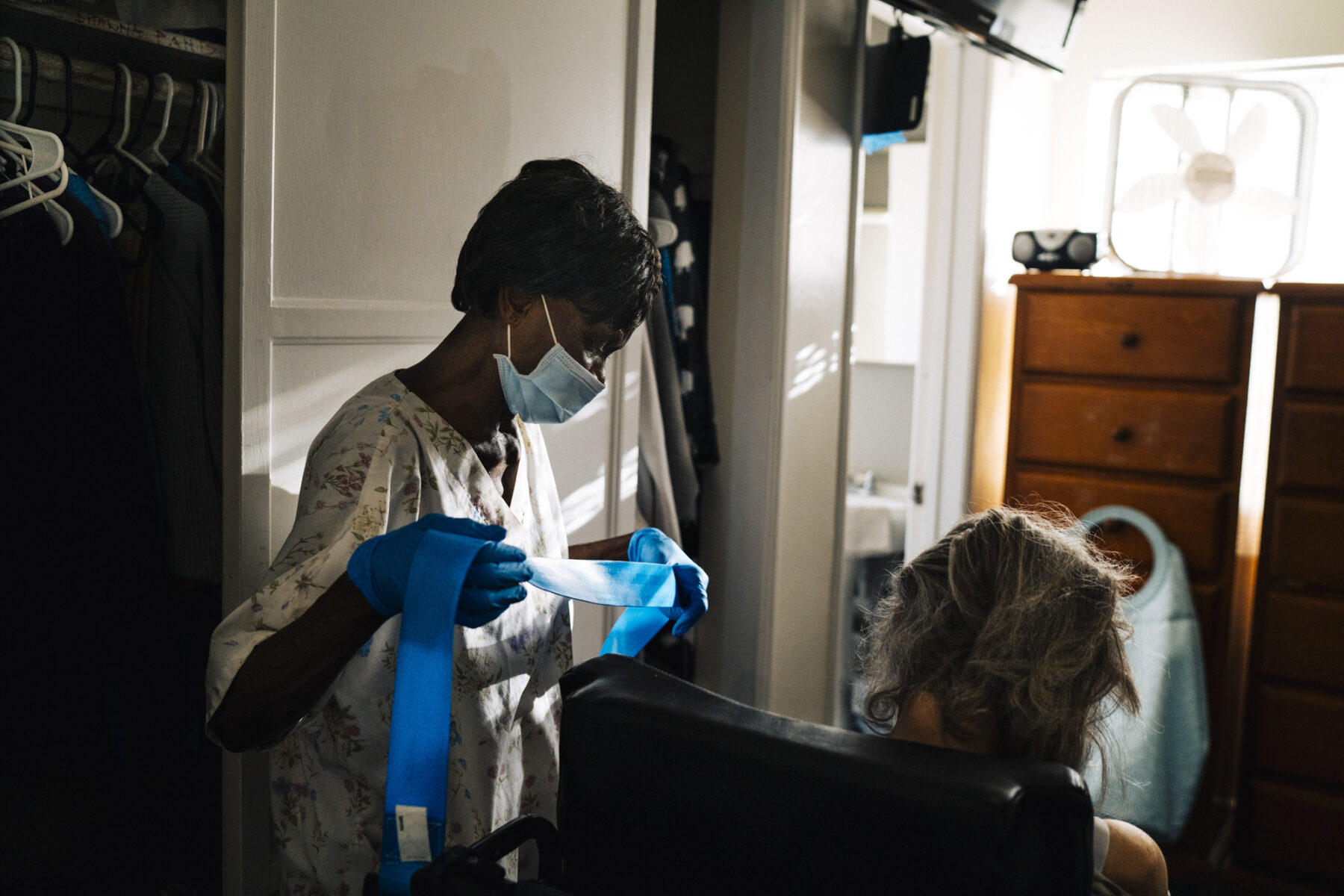

The home is funded through Medi-Cal, California’s Medicaid program. For the most part, Ann’s health care providers all see her at her home. Her medications are also delivered directly to her.

At-home services allow for minimal stress and disruption. “It is definitely the ideal model to have service providers be able to come into the house, especially when mobility is an issue and transportation is an issue,” said Darlene. Ann only needs to go to appointments at medical centers three times per year.

Most Americans are like Ann: They would prefer to receive long-term care in their home or community. For many Americans, Medicaid eligibility provides the only opportunity to afford these kinds of services when they need them.

Transportation is a major hurdle for Ann in getting to appointments. For Ann, an ACCESS ride — door-to-door transportation for adults with disabilities — is three times longer than a trip in a conventional car.

However, there are also barriers associated with Medicaid. Residents of group homes who solely have Medi-Cal often contend with a dearth of service providers who are willing to see them. Providers are sometimes more willing to accept Medicare patients, given the higher payment rates associated with this insurance program.

“She is lucky to have access to both [Medicare and Medicaid],” said

Darlene, the home’s administrator. “It opens up some more avenues for

her, especially if she wants to see a specialist.” Darlene prefers that

Ann go out mainly for education or leisure.

Transportation is a major hurdle for Ann in getting to appointments. For Ann, an ACCESS ride — door-to-door transportation for adults with disabilities — is three times longer than a trip in a conventional car.

Ann’s wellness isn’t only about her health care, but also about the activities that bring her joy and stoke her creativity. Every weekday morning, Ann attends AbleArtsWork, an art and music day program for adults with developmental disabilities located in a converted warehouse.

In a studio with piano, drums, and a record-covered wall, Mollie, a music therapist, plays an acoustic guitar as she kneels in front of each participant and sings, “Hello, how are you today?” She adds their names in turn, followed with harmony singing.

Ann reacts most enthusiastically to classical and jazz piano. During a remote class, Ann’s wandering gaze focuses sharply on her tablet when an instructor announces that he will play an excerpt of a Mozart concerto.

Ann also participates in visual arts activities. “It is where I’ve seen her voice come out the most,” said Stephanie, Ann’s long-term visual arts instructor.

Ann’s strength is two-dimensional collage; she often cuts photographs

of babies in various emotional states from magazines and pastes them in

the center of the page. Her collage work expresses a layered language

around innocence, hunger, femininity, and luminance. Her pieces contain

recurring images of able-bodied women, food, children, and lightbulbs.

As if constructing a collage of her own, care supervisor Darlene over the years has woven together strands of information to understand Ann’s needs and preferences. Darlene helps make decisions on Ann’s behalf, along with a case manager at Regional Center, an agency contracted through the California Department of Disability. When it comes to serious medical decisions, a physician through Regional Center is involved in the conversation.

All people, but especially those with complex needs like dual-eligible individuals, need support to navigate their care. Studies from the Health and MIND Institute at the University of California Davis reveal that supported decision-making from trusted partners can provide a sense of self-determination and autonomy. The majority of dual-eligible enrollees who have an intellectual disability rely on designated representatives or family caregivers to manage their care.

Ann often says only a few words each day; her main form of communication is touch. Her affection for others comes forth in her enveloping, locked embraces in which she wraps her arms around a person’s head, often for a few minutes. Physical closeness is Ann’s main form of expression with those she cares about the most, and she primarily embraces other women. One afternoon, Norberta, her neighbor from across the hall, wheeled herself past Ann. Happy to see Norberta, Ann reached forward for a hug. Norberta shook her head and quickly rolled herself away. Ann was not discouraged. She continued to smile. She knew someone else would want her embrace.

“She is the love bug of the house,” said Darlene.

The home is a subtle space of women empowerment where women providers

are in conversation with women residents about their needs. During the

last three years of the pandemic, these forged bonds were even more

vital, as residents were cut off entirely from their outside routines

and communities.

The pandemic was particularly harsh for residents of intermediate and

long-term care communities. Residents of the home who were easily

stimulated preferred the isolation, while the lack of social connection

stunted other residents, like Ann, who thrive on social interaction.

Ann has lived in Southern California congregate living for at least 20 years. Prior to moving into her current community, she lived at a large developmental center in Orange County that took an institutional approach to those with developmental disabilities. The facility is now closed. Individual group homes allow residents to feel like they are living in a house, like anyone else, with support.

When Ann moved from her previous residence, she almost never spoke. Most care providers did not know she could verbally communicate. “I had to convince people that she could speak,” said Darlene. Over the past 15 years, as Ann has grown to feel safer, she has flourished and resumed using her own voice.

Care providers now interact with Ann through short phrases and facial expressions. They encourage her to use her words and make her own choices, starting with deciding between a red or pink shirt in the morning.

“I’ve noticed that she’s really finding her voice,” said Darlene. “I think it's still a process, and she’s still growing.”

Untangling the Net is Possible

Melissa and Ann's experiences reflect flaws in the U.S. health care system that Arnold Ventures and its partners seek to address. Join us to learn more about what's possible:

Who is the dual-eligible population and what are their needs?

Production: Arnold Ventures, CatchLight, Upstatement, and Perkins Access

Photography and story: Isadora Kosofsky